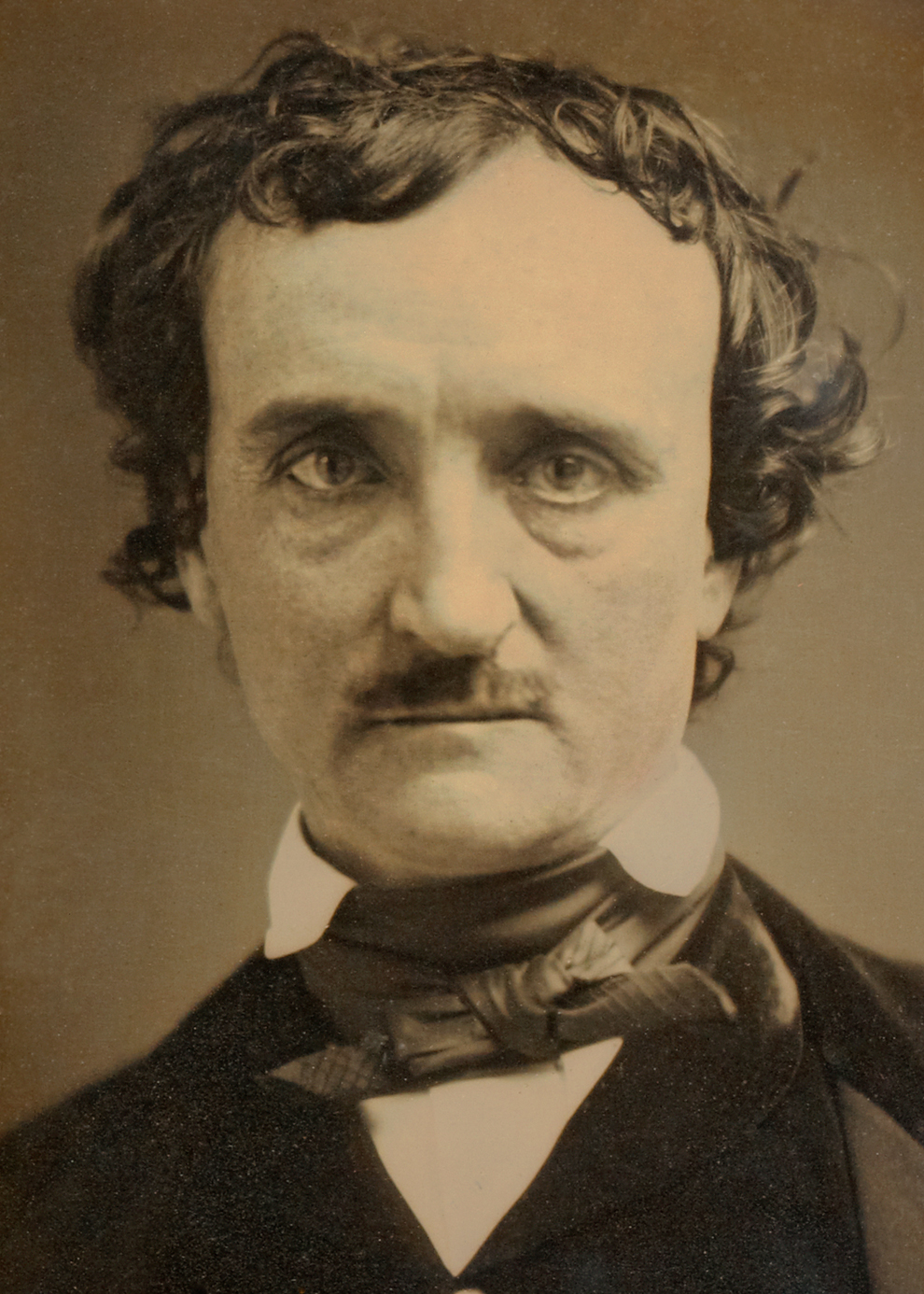

EDGAR ALLAN POE

(1809 - 1847)

BOOKS ::: AUTHOR ::: BOSTON 400

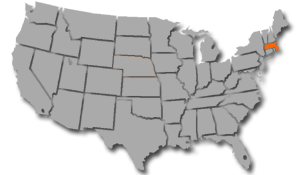

On January 19, 1809, Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston, a city that would later claim him uneasily — proud of the origin, uncomfortable with the legacy. Poe entered the world already marked by instability: orphaned young, shuffled between guardians, and haunted by precarity from the start. Boston gave him birth but not belonging; that tension — between origin and exile — would become one of the defining motors of his work. He didn’t just write about alienation and dread; he lived them.

Poe went on to invent, almost single-handedly, several modern literary forms: the psychological horror story, the detective tale, and a new, obsessive kind of lyric poetry that tunneled inward rather than soaring outward. His work fixated on unreliable narrators, decaying minds, premature burial, obsession, grief, and the thin membrane between reason and madness. Poems like “The Raven” and stories like “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” didn’t simply entertain — they diagnosed. Poe treated the human psyche as a crime scene, the soul as something to be anatomized under harsh light.

Boston would spend generations arguing over Poe — whether to embrace him or distance itself from his darkness — but that unease is precisely the point. Poe represents the underside of American optimism: the anxiety beneath progress, the rot beneath refinement, the shadow cast by reason when it stares too long at itself. In a culture that prefers uplift, Poe insisted on descent. Born in Boston, claimed everywhere, he remains one of America’s most uncomfortable geniuses — a writer who understood that the real horror isn’t the monster at the door, but the one already inside the room.