THE FALL AND RISE OF IDLEWILD: PART I

1964 demise of Michigan’s all-black resort, Idlewild, creates an eye opening moment when you slightly shift the prism toward a different angle. In what is memorialized as the bright moment in the history of post-slavery race relations in the United States of America, the 1964 Civil Rights Act was on the other hand an economic wolf in sheep’s clothing.

In the Jim Crow years that followed the American Civil War, this country operated as a backhanded compliment that offered up a “separate but equal” standard.

African-Americans were still living in a whites-only/blacks-only world where black owned businesses and black consumerism were tied at the hip. The only place a black housewife could do her shopping would be within the confines of the local community. The only good to come of this was the rise of black wealth among pillar businesses. The local grocery store owner, the local gas station, the doctor, the dentist, all thrived within this vacuum as a new generation of financially successful businessmen and women emerged.

When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed by Congress, the dazzle of the shiny object was a distraction to a new reality that many within these communities never saw coming.

Suddenly you are free to travel as you please and now you too are targeted to enjoy the luxury of cheaper costs of goods and services once only available to white folks. In one day, this seismic shift in human rights single-handedly evaporated the cash flow into these thriving, isolated markets and companies leaving the remnants of black Main Street businesses in the wake.

It was the beginning of the end of this American cultural phenomenon.

This wild ride began in 1912 when Erastus G. Branch began his three year stint in a makeshift camp in the Michigan wilds as a prequalification to establish ownership via the old school methodology of land acquisition known as homesteading. Once the land deed became official, he and his business partners set forth in their vision to establish an all-black midwest resort. They were white and they were religious and they named the destination, Idlewild. Legend has it that it would be the getaway for idle men and wild women.

Idlewild experienced its first population boom in the days following World War I as a seasonal escape that lasted from Memorial Day to Labor Day. By the 1920s, the resort expanded into a year round affair. It was an earlier fuzzy version of timeshare with families snatching up lots of land and cabins.

Before long, a group of black investors led by the world’s first open heart surgeon, Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, made Idlewild a black owned business. Luminaries and political powerhouses rubbed elbows in peak season. Entrepreneur Madame CJ Walker, NAACP founder WEB DuBois, Dr. Fannie Emanuel, members of Marcus Garvey’s UNIA, disciples of Booker T. Washington and boxing great Joe Lewis all held court.

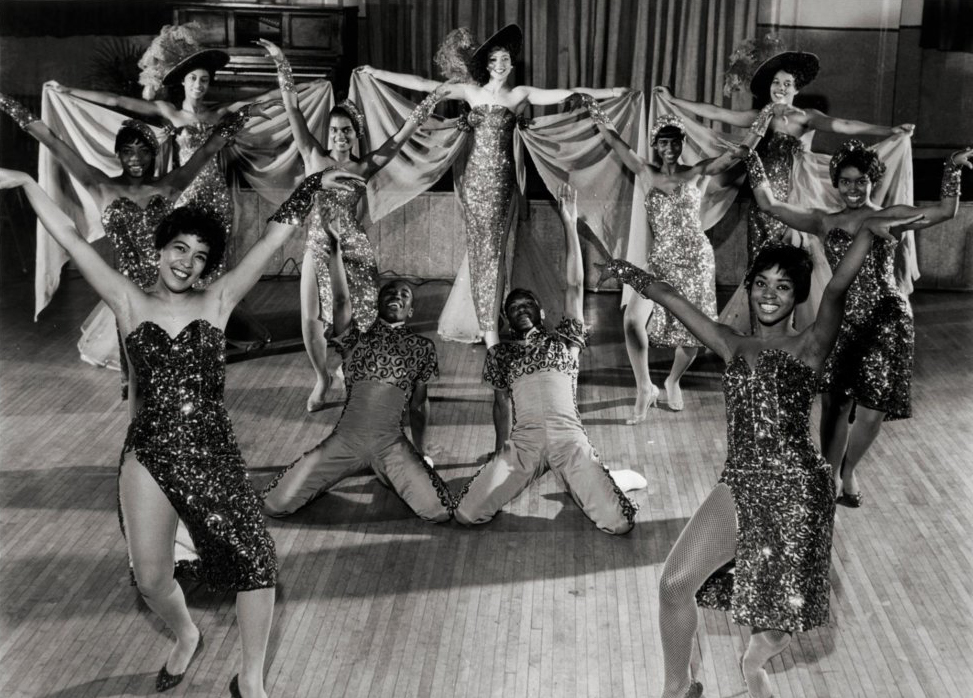

But segregation still had its stranglehold on the world of black entertainers who were relegated to travel a cobbled map of black only night clubs across the country known as the “chitlin’ circuit.” The greatest black entertainers of the time who “made it” cited their appearances at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom and Apollo Theater, Chicago’s swanky entertainment districts and Idlewild as the badge of their success.

Idlewild earned itself nicknames such as the “Mecca of Black Success” and “Black Eden.”

By the mid-fifties, Idlewild’s hotspots, the Flamingo Club and the Paradise Club, were in all their glory. They say that any entertainer who was worth his or her salt graced the Idlewild stages.

The list is both long and breathtaking. Cab Calloway. Sarah Vaughn, Duke Ellington, Aretha Franklin, the Four Tops, Jackie Wilson, Arthur Prysock, Fats Waller, Sammy Davis, Jr., Bebop Carter, Al Hibbler, Dinah Washington, Temptations, James Brown, Brooks Benton, Dionne Warwick., George Kirby, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, The Midnighters, Della Reese, T Bone Walker and BB King.

Summer days and nights featured beauty pageants, literary circles, skating rinks and hunting clubs while communities within the communities sprung up representing St Louis, Detroit and Chicago.

In 1964, came the Civil Rights Act.

Dr. Benjamin C. Wilson, professor emeritus of Africana studies, notes that the story of Idlewild marks an indelible moment in the history of the Black American experience and Idlewild’s resume serves as the backbone of pop culture. We think he’s correct. Join us this spring as our Idlewild adventure unfolds.