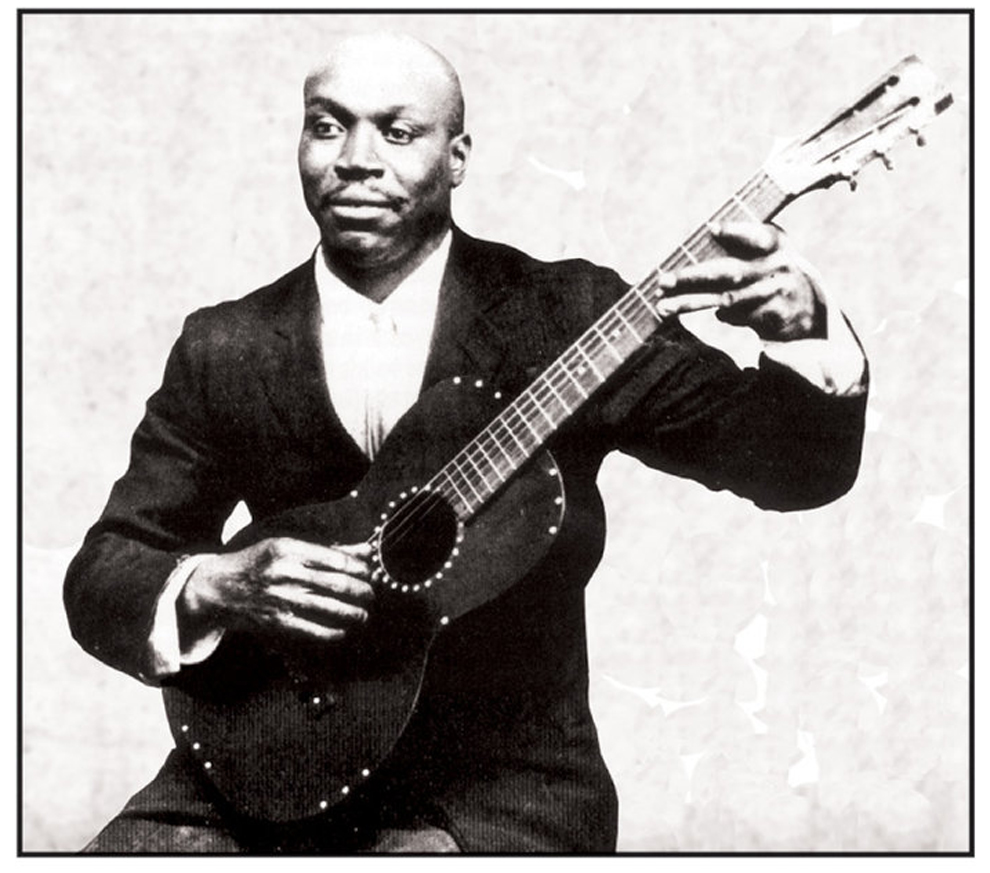

CHARLEY JORDAN

(1890–1954)

MUSIC ::: BLUES

Charley Jordan sang the blues from inside the conditions that created them. A street-level singer, songwriter, and guitarist active in St. Louis during the 1930s, Jordan belonged to a generation of urban bluesmen whose music was shaped by sidewalks, rooming houses, police pressure, and the economics of survival.

His songs are plainspoken, conversational, and unsentimental—less performance than reportage. Jordan didn’t mythologize hardship. He stated it.

In 1928, Jordan was shot during the Prohibition era, an incident widely cited in blues discographies and reissue liner notes as connected to bootlegging activity. The bullet lodged in his spine, leaving him permanently disabled; later photographs show him walking with crutches. The circumstances of the shooting—who fired the shot, where it occurred, and why—were never preserved in the public record.

What remains is consequence.

Most of Jordan’s known recordings come after the injury, lending his work a literal weight. Songs like Starvation Blues are not metaphorical accounts of the Great Depression; they are post-trauma documents, addressing hunger, immobility, and endurance without ornament.

Jordan’s St. Louis blues favors conversational vocals, rhythmic, functional guitar, humor and innuendo as survival tools Like Memphis Minnie and Big Joe Williams, he worked close to the edge of the everyday—where wit and grit were forms of currency.

Jordan’s biography contains gaps typical of working-class Black artists of the early 20th century. Violence, injury, and extramusical labor appear briefly—then disappear. The silence surrounding his shooting is part of the story: damage absorbed, unremarked by institutions, carried forward in song.

Charley Jordan matters because his recordings function as an unsanitized archive of Depression-era America. They document what happens when the system fails and culture adapts in real time.

No polish.

No distance.

No redemption arc.Just a man, a guitar, and the truth—

recorded so history couldn’t say it didn’t know.